- Home

- Capps1

Source: CAPPS.pdf

Paroling people who committed serious crimes:

What is the actual risk?

Barbara Levine, Associate Director

Elsie Kettunen, Data Analyst

Citizens Alliance on Prisons & Public Spending

December 1, 2014

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

Executive Summary

The Michigan parole board routinely continues, i.e. declines to parole, prisoners who have served their judicially imposed minimum sentences and are eligible for release.

Thousands are continued four, five, six times or more at great cost to taxpayers as well as to the prisoners and their families.

Many of those denied score favorably on the Michigan Department of Corrections’ (MDOC) parole guidelines and other risk assessment instruments.

A large proportion was convicted of homicide or sex offenses. They are continued because, based on their crimes, they are perceived to be a risk to public safety.

Decades of research in Michigan and other jurisdictions shows:

•People who commit homicides or sex offenses have extremely low

•There is no evidence that keeping someone incarcerated longer increases public safety.

This research is confirmed by the very low

•Of 820 people who had been serving for murder or manslaughter, two (0.2 percent) returned to prison for a new homicide.

•Of 4,109 people who had been serving for a sex offense, 32 (0.8 percent) returned to prison for a new sex offense.

In fact, in 2009 and 2010, returns to prison with new sentences actually decreased, despite the release of more than 1,000 additional people serving for homicide and sex offenses as a result of the parole board’s continuance review process.

Introduction

In 2009, in an effort to address Michigan’s $2 billion corrections budget by reducing the prisoner population, Gov. Jennifer Granholm expanded the parole board. The idea was that with more capacity it could increase the number of prisoner releases. The board reviewed thousands of prisoners who had served their minimum sentences and were eligible for parole but who had previously been “continued,” that is, denied release. Many of these denials occurred despite favorable scores on the Michigan Department of Corrections’ own parole guidelines and were based primarily on the seriousness of the offense.

Some in law enforcement denounced the move, saying that Granholm was trying to save money at the expense of public safety. They pointed to the release of people who had committed murder and sex offenses and predicted dire consequences.

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 2

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

By the end of 2009, the total number of people paroled had reached 13,508, an increase of 2,020 over the year before. The number of homicide offenders paroled more than doubled from 197 to 409. The number of sex offenders also doubled from 906 to 1,855. For people convicted of sex offenses, the trend toward more releases continued into 2010, when 742 were paroled in the first three months.

This paper examines the results of that endeavor and explores the larger questions it raises about the relationship between parole and public safety.i

The 2009 releases

The MDOC routinely reports on parolees who returned to prison with a new sentence within three years of their release.ii The department’s 2013 Statistical Report shows everyone who paroled to a Michigan county in each year from

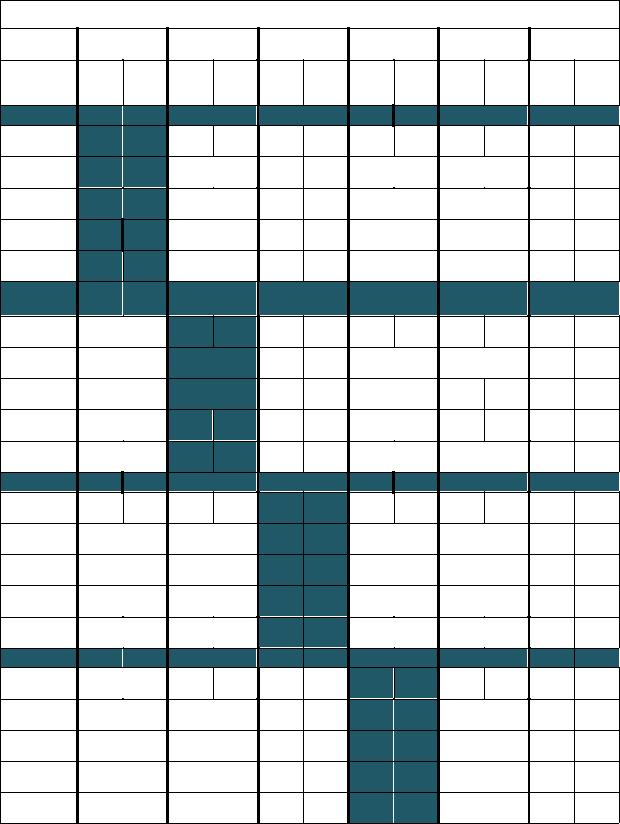

As Table 1 shows, the new sentence rate for 2009 parolees was lower than it had been for those

released in the preceding nine years, at 15.6 percent. It was more than two points lower than for people released in 2008. Increasing the number of paroles clearly did not increase the re- offense rate.

Table 1. Percent of New Sentences among Total Paroles

|

Total |

Percent |

|

Year |

Total |

Percent |

Year |

Cases |

New |

|

|

Cases |

New |

|

|

Sentence |

|

|

|

Sentence |

1998 |

10,055 |

16.1 |

|

2005 |

9,801 |

21.1 |

1999 |

9,276 |

14.8 |

|

2006 |

9,694 |

21.3 |

2000 |

8,709 |

16.4 |

|

2007 |

11,805 |

19.7 |

2001 |

9,591 |

17.3 |

|

2008 |

11,044 |

17.9 |

2002 |

10,254 |

18.2 |

|

2009 |

12,829 |

15.6 |

2003 |

11,207 |

18.7 |

|

2010 |

11,552 |

13.5 |

2004 |

10,818 |

19.9 |

|

|

|

|

To better understand the impact of the continuance reviews, CAPPS looked at all the people who were paroled in 2007, 2008, 2009 and the first quarter of 2010 after having served sentences for homicide

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 3

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

The first and last columns of Table 2 reveal three broad points about these offenses:

•The percent of people who returned with new sentences was lower for those released in 2009 than in the two preceding years for each offense group.

•Over 95 percent of the people serving for homicide and sex offenses who were released in 2009 did not return with a new sentence for any crime within three years.

•

Table 2 also shows the nature of the new offenses for which people returned to prison. Looking at the number of new sentences and the percentage they constitute of total releases, it is apparent that few people paroled on very serious crimes return with convictions for similar offenses.

•People paroled on homicide offenses virtually never return to prison within three years for another homicide, assault with intent to murder or a sex offense.

•People paroled on assault with intent to murder sentences show a similar pattern, although at 6.8 percent their return rate for “other” offenses is a bit higher than that of the homicide offenders.

•Sex offenders have the lowest return rate for a new crime of any type.

oContrary to popular assumptions, people paroled on a sex offenses rarely return to prison for another sex offense.

oOf more than 4,100 people paroled on a sex offense during the 39 months under review, only 32 – less than 1 percent

•People convicted of robbery are more likely to return with a new sentence for the same crime than others paroled on serious crimes. Yet 95 percent of those paroled on a robbery offense do not return with a new sentence for another robbery.

oThey were roughly three times more likely than homicide and sex offenders to return for such offenses as burglary, larceny, drugs or weapons possession.

oOf the 4,110 robbery offenders released during the

These low

The MDOC published

Among people who committed person offenses,

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 4

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

Table 2. Frequency of New Offense Types

New Sentence Offense

|

Homicide |

Assault/ |

CSC |

Robbery |

Other |

Total |

||||||

|

|

|

Murder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Conviction |

No. |

% of |

No. |

% of |

No. |

% of |

No. |

% of |

No. |

% of |

No. |

% of |

Offense |

New |

Total |

New |

Total |

New |

Total |

New |

Total |

New |

Total |

New |

Total |

|

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Sent. |

Rel’d |

Homicide |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2007 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.6 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.6 |

8 |

5.0 |

10 |

6.2 |

N = 161 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

1 |

0.5 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.5 |

2 |

1.0 |

12 |

6.1 |

16 |

8.1 |

N = 197 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2009 |

1 |

0.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.2 |

3 |

0.7 |

13 |

3.2 |

18 |

4.4 |

N = 409 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

1.9 |

2 |

3.8 |

3 |

5.7 |

N = 53 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

2 |

0.2 |

1 |

0.1 |

2 |

0.2 |

7 |

0.9 |

35 |

4.3 |

47 |

5.7 |

N = 820 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assault/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Murder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2007 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.8 |

2 |

1.6 |

9 |

7.0 |

12 |

9.4 |

N = 128 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.9 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

9 |

8.4 |

10 |

9.3 |

N = 107 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2009 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

2 |

1.4 |

1 |

0.7 |

8 |

5.7 |

11 |

7.8 |

N = 141 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

4.3 |

1 |

4.3 |

2 |

8.7 |

N = 23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

0 |

0.0 |

1 |

0.3 |

3 |

0.8 |

4 |

1.0 |

27 |

6.8 |

35 |

8.8 |

N = 399 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CSC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2007 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

6 |

1.0 |

2 |

0.3 |

36 |

5.9 |

44 |

7.3 |

N = 606 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

8 |

0.9 |

0 |

0.0 |

40 |

4.4 |

48 |

5.3 |

N = 906 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2009 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

13 |

0.7 |

5 |

0.3 |

65 |

3.5 |

83 |

4.5 |

N = 1,855 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

5 |

0.7 |

1 |

0.1 |

12 |

1.6 |

18 |

2.4 |

N = 742 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

32 |

0.8 |

8 |

0.2 |

153 |

3.7 |

193 |

4.7 |

N = 4,109 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Robbery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2007 |

1 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

68 |

4.9 |

185 |

13.3 |

254 |

18.2 |

N = 1,396 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2008 |

3 |

0.2 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

53 |

4.4 |

178 |

14.8 |

234 |

19.5 |

N = 1,203 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2009 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

45 |

3.6 |

161 |

12.9 |

206 |

16.5 |

N = 1,249 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2010 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

13 |

5.0 |

27 |

10.3 |

40 |

15.3 |

N = 262 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

4 |

0.1 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

179 |

4.4 |

551 |

13.4 |

734 |

17.9 |

N = 4,110 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 5

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

paroled from homicide sentences and 10 percent of those paroled from sex offenses returned with a new sentence for any crime.

For several decades, the MDOC also provided data about the kinds of new crimes parolees committed. Thus Table 3 also enables us to see the extent to which serious offenders returned to prison for committing the same type of offense again. The short answer is: rarely.

Table 3.

Cohort |

Total New Sentence Rate |

|

New Sentence for Same Crime |

|||||||

|

Homicide |

Rape/CSC |

Assault |

Robbery |

|

|

Homicide |

Rape/CSC |

Assault |

Robbery |

1960 |

1.6% |

5.5% |

8.2% |

17.1% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1970 |

3.4% |

2.7% |

14.3% |

12.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1980 |

5.9% |

9.9% |

14.8% |

16.6% |

|

|

0.4% |

0.4% |

2.0% |

4.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1990 |

6.3% |

6.8% |

12.5% |

17.2% |

|

|

1.0% |

2.5% |

4.1% |

5.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2000 |

5.4% |

3.8% |

8.0% |

16.0% |

|

|

0.5% |

1.9% |

2.3% |

3.2% |

A study published by CAPPS in 2009 examined the extent to which released prisoners returned with new offenses within four years. Denying Parole at First Eligibility: How Much Public Safety does it Actually Buy? reported on nearly 77,000 cases of people first paroled from

Overall, the study found that 18 percent of all released prisoners returned with sentences for new crimes. However, homicide and sex offenders had rates of return with new sentences below eight percent. And all of the most serious offenses showed extremely low rates of repeating the offense of conviction. During this

•Of 6,673 sex offenders, 204 (3.1 percent) returned with a new sex offense.

•Of 2,448 homicide offenders, 14 (0.5 percent) returned for a new homicide.

The CAPPS report also summarized numerous studies from other jurisdictions. These studies consistently found that reoffending is highest for property offenses and lowest for homicide and sex offenses. Eight of nine that looked at recidivism rates for sex offenders found that the rate for returning to prison for a new sex offense was 3.5 percent or less.iii

In sum, a wealth of evidence going back decades, from Michigan and many other states, shows that the very low

Examining the Continuances

Studies have also consistently shown there is no correlation between keeping people incarcerated longer and their likelihood of reoffending.iv Why, then, do we deny release to thousands of people who have served their minimum sentences? What are the costs and the benefits?

The available data did not allow for examination of exactly how long beyond their minimum sentences the

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 6

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

24 months before he or she is reviewed again. The frequency of continuances for people who committed offenses against people is remarkable.

•27 percent were released upon serving their minimum sentence.

•22 percent were continued just once.

•14 percent were continued twice.

Of the remaining 37 percent (a total of 3,479):

•1,042 had been continued three times.

•766 had been continued four times.

•558 had been continued five times.

•384 had been continued six times.

•729 had been continued seven times or more.

Even if each continuance was only for one year, a conservative estimate, it is evident that thousands of people spent many years longer in prison than their judicially imposed minimum sentences required.

Table 4 shows the frequency of continuances by offense type. The differences are extreme.

Robbery offenses had the fewest continuances:

•More than 40 percent were paroled on their minimums.

•More than 63 percent had no more than one continuance.

•Fewer than 20 percent had been continued four or more times.

•Note: The proportions are quite similar for those convicted of assault with intent to murder.

Sex offenses had by far the most:

•Only 12.4 percent were paroled on their minimums.

•33.4 percent had no more than one continuance.

•Nearly 34 percent had been continued four or more times.

The number of continuances was substantially higher for people released as part of the continuance review process:

•Among those paroled in 2007 and 2008, 18 percent were paroled on their minimums.

•Among those paroled in 2009 and 2010, the proportion dropped to 10 percent and eight percent, respectively.

•By 2010, 40 percent had been continued four or more times.

Homicide offenders also had a much lower chance of being released at their minimum and a greater chance of being continued repeatedly:

•Fewer than half had no more than one continuance.

•Nearly one quarter had been continued four or more times.

•The percentage paroled on the minimum declined from more than 30 percent in 2007 and 2008 to 24 percent in 2009 and 22.6 percent in 2010.

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 7

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

Table 4. Continuances by Offense Type

|

|

|

Continuances |

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

3 |

4+ |

Homicide |

26.7% |

20.9% |

15.2% |

|

12.0% |

23.4% |

Assault/Murder |

38.1% |

24.1% |

12.3% |

|

9.8% |

15.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CSC |

12.6% |

20.8% |

17.8% |

|

14.8% |

33.9% |

Robbery |

40.5% |

22.9% |

10.6% |

|

7.2% |

18.8% |

Table 5 explores whether keeping people incarcerated longer reduces their likelihood of returning with a new sentence. The answer is no. There is no correlation between how often people are continued and whether they reoffend.

•Homicide:

•Assault with intent to murder: 94 percent of those who were not continued at all and those who were continued four or more times did not return with new sentences.

Note: Although these cases show some variation, the small number of people who returned with a new sentence causes the percentages to be exaggerated.

•Sex offenses: Nearly

•Robbery offenses: Although the robbery offenders had higher

Table 5. Continuances by New Sentence “No” and “Yes”

|

|

|

|

Continuances |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4+ |

|

Homicide |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No (N = 773) |

|

93.6% |

94.2% |

|

96.0% |

92.9% |

94.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes (N = 47) |

|

6.4% |

5.8% |

|

4.0% |

7.1% |

5.3% |

Assault/Murder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No (N = 364) |

|

94.1% |

91.7% |

|

81.6% |

87.2% |

93.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes (N = 35) |

|

5.9% |

8.3% |

|

18.4% |

12.8% |

6.3% |

CSC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No (N = 3,916) |

|

93.6% |

94.2% |

|

97.0% |

96.6% |

95.2% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes (N = 193) |

|

6.4% |

5.8% |

|

3.0% |

3.4% |

4.8% |

Robbery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No (N = 3,376) |

|

83.7% |

81.4% |

|

80.6% |

78.6% |

81.8% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes (N = 734) |

|

16.3% |

18.6% |

|

19.4% |

21.4% |

18.2% |

MCL 791.233e requires the development of guidelines to aid the parole board in deciding whom to release. People who achieve a certain point total are considered “high probability of release.” They are supposed to be paroled unless the board has “substantial and compelling reasons” to depart

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 8

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

from the guidelines recommendation. While the guidelines assign points for various factors known to predict

By administrative rule, the parole guidelines are designed so that people who score high probability of release do not exceed an assaultive felony recidivism rate of more than 5 percent. R. 716 (2). Thus it is to be expected that people who score high probability of release will have a lower overall rate of returns to prison with new sentences.

More noteworthy is the relatively low rate of new sentences among people with average probability scores, especially those who had committed homicide and sex offenses. Table 6 shows that the difference in

Table 6. Percentage of Returns with Any New Sentence by Parole Guidelines Score

|

High Probability of Release |

Average Probability of Release |

Homicide |

4.3% |

10.3% |

|

|

|

Assault with intent to murder |

6.4% |

13.6% |

Criminal Sexual Conduct |

2.7% |

6.7% |

Robbery |

14.5% |

20.9% |

|

|

|

The data clearly show that:

•There are thousands of continuances annually.

•The number of continuances does not correlate with

•The parole guidelines score does correlate with reoffending.

That still leaves two important questions:

1.How does the number of continuances relate to parole guidelines scores? That is, how often are people with high probability scores continued?

2.Are people who score high probability continued less often than those who score average probability?

Table 7 shows that for three of the four offense groups, people with high probability scores are substantially more likely than those with average scores to be released on their minimum and less likely to be continued four or more times. However:

•For people continued one, two or three times, the differences in releases between the high and average probability cases were much smaller.

•The sex offense group is an exception. Not only were the differences between the high and average probability cases very small across the board, those who scored average probability actually fared better. They had a larger proportion with no more than one continuance and a smaller share that was continued four or more times.

Table 7 also shows that a substantial portion of people who score high probability of release are continued repeatedly.

•For those convicted of sex offenses, the proportion of high probability cases with four or more continuances was nearly 36 percent. Only 11.3 percent were released on their minimums. Fewer than

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 9

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

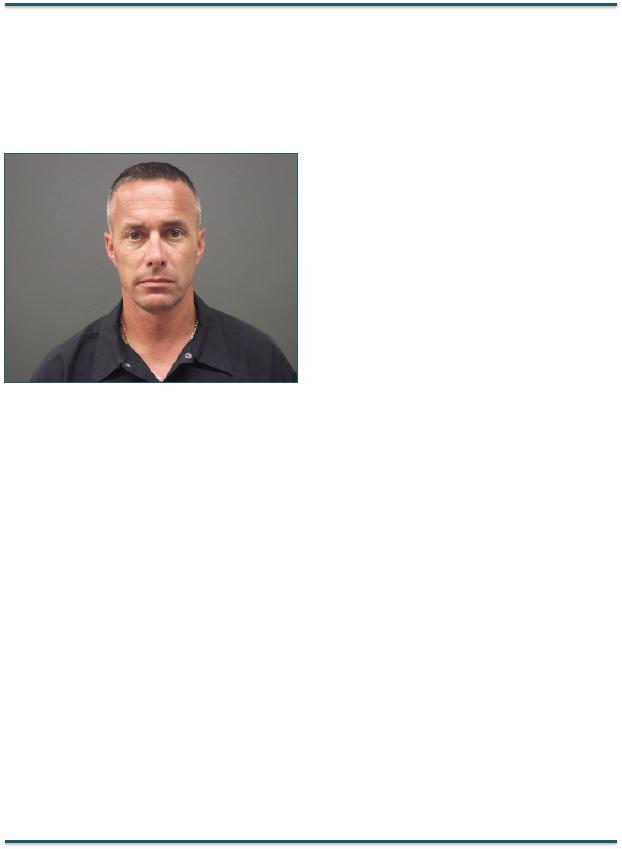

Anatomy of a continuance: Ronald Webb

There is no dispute that Ronald Webb’s father was physically and emotionally abusive. His parents divorced when Webb was age 10. Webb lived primarily with his father, with whom he had a “love/hate relationship.” Webb’s school performance suffered and his acting out caused his mother to seek family counseling. By the age of 14, Webb had developed a substantial pattern of substance abuse. His criminal record consisted of a few thefts but no history of violence.

In Nov. 1990, when Webb was 19, he killed his father and his father’s girlfriend with a shotgun. He was charged with two counts of open murder. A Jackson County jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity for his father’s death and guilty of

Despite his difficult childhood and the jury’s verdicts that found him mentally ill, Webb received no sort of therapy when he entered

prison. However he adjusted well. His work, school and program reports are excellent, his misconduct history is not serious and he is housed in a minimum security facility.

Webb, now 43, first became eligible for release on August 1, 2013. In preparation for parole consideration, risk assessment instruments were scored and the parole board requested a psychological evaluation. The COMPAS Risk Assessment showed Webb to be low for violence, low for recidivism and low for recommended level of supervision. His parole guidelines score was “high probability of release.” The psychologist found no evidence of mental illness. Webb has the full support of his mother and sisters and the promise of a job upon release.

On May 17, 2013, Webb was continued for one year because he had not been able to complete programming the board felt he should have. In

Webb was interviewed by a single board member. Notes in the file confirm what Webb and his mother were told: The interviewing member believed that, regardless of the jury’s verdict, Webb was actually guilty of two counts of premeditated murder.

On May 2, 2014, the board continued Webb again, this time for 24 months. The substantial and compelling reasons given for departing from the parole guidelines were:

“Prisoner failed to take responsibility for his violent actions and minimized his behavior, blames others for his anger. The P[arole] B[oard] does not have reasonable assurance at this time that P’s risk is reduced. “

Webb’s next consideration date will be August 10, 2016.

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 10

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

•Among those convicted of homicide, nearly a quarter of the high probability cases were continued four or more times. Only 26 percent were released on their minimums. More than 50 percent had been continued more than once.

•For those convicted of assault with intent to murder and robbery, about 12 percent of those scoring high probability of release were continued four times or more.

It is apparent from the data that the parole board considers the nature of the offense to be a “substantial and compelling reason” for denying release to a prisoner who is low risk to release. The nature of the offense is the primary factor considered by the court in setting the minimum sentence. Thus the board is extending the incarceration of thousands of prisoners, based on its own view of the appropriate punishment, not on an assessment of actual risk.

Table 7. Continuances by Parole Guidelines Score

|

|

|

|

Continuances |

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Homicide |

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

|

25.9% |

21.1% |

17.5% |

12.1% |

23.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

19.6% |

23.0% |

10.8% |

12.7% |

33.8% |

Assault/Murder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

|

40.6% |

25.9% |

12.8% |

9.0% |

11.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

32.6% |

20.5% |

11.4% |

11.4% |

24.2% |

CSC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

|

11.3% |

19.8% |

18.5% |

14.9% |

35.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

13.9% |

21.9% |

17.1% |

14.9% |

32.2% |

Robbery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

|

48.1% |

25.4% |

8.2% |

5.7% |

12.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

|

30.7% |

22.0% |

13.2% |

8.8% |

25.2% |

Conclusion

People who commit murder, criminal sexual conduct and other assaultive offenses receive longer prison sentences than other offenders because of the seriousness of their crimes. Their behavior is clearly deserving of more punishment than a property or drug offense. But once they have served their minimum sentences, should these offenders be granted parole like other prisoners, based on their institutional conduct, program participation and parole guidelines scores? Or should they be denied release because they are perceived to present an ongoing threat to public safety?

The answer to these questions is central to the debate over how to control the size of the prisoner population while protecting public safety. Understandably, no parole board member wants to release someone who has caused terrible harm only to have similar harm visited on another victim. It is easier to err on the side of keeping a prisoner incarcerated longer than to face opposition based on potential or actual new offenses. But at roughly $20 million per each 1,000 prisoners, we simply cannot afford to keep

It is true that when 95 percent of a group does not reoffend, five percent do. And within that five percent there will inevitably be serious cases with tragic consequences. By definition, these will be

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 11

Issue brief: Paroling people who committed serious crimes: What is the actual risk?

cases in which the parole board exercised its discretion to grant release. In many cases, the person will have been released after serving on a

The only way to prevent any crime by parolees is to parole no one. That would mean keeping incarcerated for many years thousands of people who would never commit another crime. The cost to them, their families and communities and to taxpayers would be unbearable. Scarce resources would be diverted from services that could actually reduce victimization.

To resolve the debate over when to grant parole fairly and accurately, we must recognize that past behavior and future risks are two very different issues. Although the parole board purports to use

The data on

No one suggests releasing people on their minimums without regard to individual indicators of risk. But the conclusion to be drawn from the research is clear. There is no gain to public safety from basing parole denials on the nature of a person’s offense, most especially for people who score high probability of release on the parole guidelines.

The more

i The authors wish to thank Jeffrey Anderson of the MDOC Research Division for his patience in explaining the finer points of the Corrections Management Information System (CMIS). The conclusions reached are solely those of CAPPS.

ii Return to prison within three years is a very common method of measuring recidivism. Most parolees who fail do so sooner rather than later. The longer someone has been released, the less likely they will return with a new offense. The data includes everyone who received a new sentence within three years of release regardless of whether they were still on parole at that point. Where sufficient evidence exists to prove that a parolee has committed a new felony offense against a person, there is little doubt the parolee will be prosecuted.

The instant research looks only at returns with new sentences, not people returned for “technical” violations of conditions of supervision. The rate of technical violations is subject to change as a parole board changes its supervision and revocation policies. Michigan, for instance, changed from an era of “zero tolerance” for technical violations to a greater use of progressive

iii Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending, Denying parole at first eligibility: How much public safety does it actually buy? A study of prisoner release and recidivism in Michigan (Lansing, Aug. 2009),

ivId. at pp.

(Washington, D.C,, June 2012) at pp.

v MDOC Policy Directive 06.05.100.

Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending | 12

Source: CAPPS.pdf